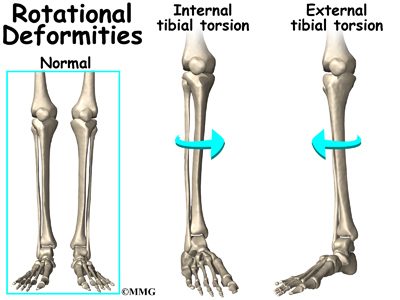

Last week I saw three different people with externally rotated knees. In particular: Three externally rotated right knees that don’t internally rotate, causing the individual some grief (not just at the knee, but definitely at the knee).

I remember Gary Ward saying something to the effect of, if you keep seeing the same thing over and over again in your practice within a short period of time, check to see if it’s not your OWN issues that you’re projecting onto your clients. Have been guilty of that in the past.

Just to make sure I’m not full of shite, I stand up, check out my right knee, and, lo and behold, it appears my right knee doesn’t fully internally rotate. Actually, both don’t. Well damn. However, my right knee internally rotates a lot more easily than my left, so, maybe my awareness, despite my imperfections, is helping to keep my perception honest. In any case, the important lesson: Whenever you see a bunch of the same thing, check to make sure it’s not just YOU.

I already wrote a little (kind of long) piece about a lady I worked with who had an internally rotated knee that wasn’t externally rotating. Her knee was actually stuck in some kind of purgatory in which it neither rotated in OR out. Maybe you’d like to read that, too (slightly different case than these three peeps).

I would like elaborate on a few observations I noted in working with these three individuals, aka, how not being able to internally rotate a knee can potentially wreak havoc on the body.

Some stuff they had in common, in particular:

- Missing an effective propulsion phase of gait

- Feet turning out in gait, aka, the “duck walk”

- Rock solid, toned up, tibialis anterior

- Low femoral external rotation

- Limited right trunk rotation

Are you ready to get excruciatingly technical? Hell yeah!

LACKING PROPULSION

Propulsion- The phase in the gait cycle just before the foot picks up off the ground prior to swing in which the pelvis is travelling (propelling, if you will) forwards, the extending hip fully decompressing, and the foot is in a maximally supinated , rigid lever position. To create this rigid lever, the knee also needs to be locked in extension in order to anchor the foot to the ground so that the pelvis can travel forwards, allowing the hip to extend and load the hip flexors for the next moment: Swing.

Getting to propulsion effectively is important.

However, in all three of my funky-kneed individuals, propulsion was just not happening.

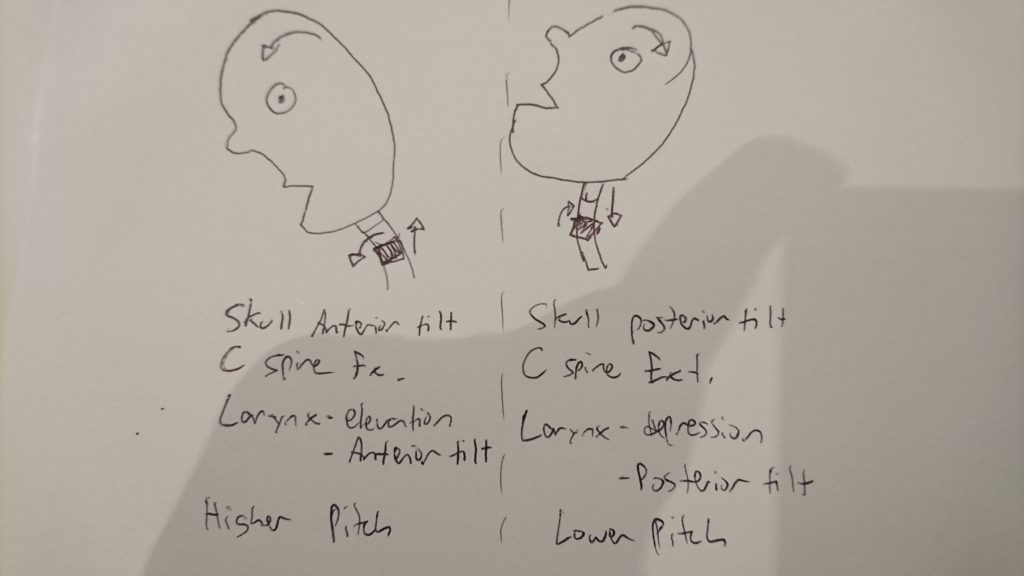

In propulsion, the knee will be in its end range of extension. For this to happen, the femur twists externally on top of the tibia, locking the condyles together into it’s “screwed home”, comfy position (home= comfy). This creates a position in which the tibial tuberosity is rotated medially of the femur, giving us an internally rotated knee.

Knee extension = knee internal rotation in an ideal situation in gait.

If the knee can’t get “home” to internal rotation and extension, as was the case for these three individuals, then the rigid lever to propel off of will be compromised, and resultant shite: The hip won’t extend, swing may be compromised, and all the muscles that load up in propulsion (psoas, iliacus, distal tibialis anterior, peroneals, distal hamstrings, distal FHL, adductors, to name some biggies), will not get their chance to lengthen.

Internally rotatable knees= Happy hips that can extend.

FEET TURNING OUT IN GAIT

That funny “duck” walk thing. I used to do that. And then I stopped ballet…

A little experiment you can try. Standing bilaterally, turn your feet out. Can you feel which way your talus is now pointing? If you are a normal human being, you should feel that feet out= sub-talar joint axis (STJ) pushes in. The opposite is true if you stand with your feet pointing inwards- STJ will point out.

Feet pointing out in gait is often a hint towards a foot that can’t pronate, and an attempt to give the STJ an opportunity to point inwards.

In pronation, the STJ axis will orient internally of the 2nd toe (usually wayyy more internally than that). But what if the foot can’t pronate? Or, what if pronation has become dangerous for some reason, and the body has needed to find a way to work around it?

Turning out the feet is one work-around: Feet out, STJ pushes in, medial arch gets to open, brain thinks it is “pronating”, but without actually pronating.

In gait, pronation and knee external rotation happen at the same time. This means that, in the case of the already externally rotated knee that doesn’t internally rotate, pronating the foot may feel dangerous because with the knee already externally rotated, there’s nowhere further to go if the foot pronates.

If the foot does pronate, the knee will reach end range external rotation (XR) too quickly and that may not feel so good. As a strategy, the body needs to find an alternative way to get a bit of “pronation” through the foot, and tan easy way to do this is to turn the foot out so that the talus can feel like it’s pointing in, and the medial arch can open. Not ideal. Definitely a work-around, but better than not being able to walk in the short term.

If the knee was able to internally rotate, this would free some space for it to move into external rotation as the foot pronates, rather than immediately crash into end-range. The change in timing allows pronation and external rotation of the knee to couple together safely.

In the case of these individuals, reintroducing knee IR was a foreign, but nurturing experience.

ROCK SOLID TIBIALIS ANTERIOR

Tibialis anteriori? Anterior tibialises?

(also see T: Tons of tone…)

Tib ant is a cool muscle that I don’t completely understand. Its triplanar functions hurt my brain (and I still have to see some clients today who need it).

That said, I did spend about 20 minutes on my couch groaning in agony trying to make sense of tib ant, my room mate giving me strange looks (rightfully so).

Tib ant is a strange and fascinating muscle.

- It lengthens and shortens at both ends simultaneously, despite being a multi-joint muscle (which generally do NOT do this unless you want it to feel really bad).

- It shortens in two planes while lengthening in another, and visa versa (sagittal and transverse couple, while frontal opposes).

I enlisted a little help from some smart AiM friends to understand the closed chain mechanics of tib ant when the knee is interally vs externally rotated. Here is the verdict:

Knee extension + internal rotation + foot supination:

SAGITTAL: Long (except in strike phase of gait in which the ankle is actually dorsiflexed with an extended knee, and so the tib ant will be short here)

FRONTAL: Short

TRANSVERSE: Long

Knee flexion + externally rotation + foot pronation:

SAGITTAL: Short (note, this is passive shortening, as gravity does the job of dorsiflexing the ankle and pronating the foot.)

FRONTAL: Long

TRANSVERSE: Short

So, in the case of our friends with externally rotated knees and rock solid tib ant, what does this mean? Few theories for the increase in muscles density and hypertrophy:

- Length tension: Being used excessively to decelerate a joint motion. For example:

- Tib ant decelerates the arch lowering in frontal plane to manage over-pronation (aka shin splints). Slowing down pronation will serve an already externally rotated knee by preventing it from rotating further, and tib ant may be working overtime for this.

- Ankle may be plantar flexing too quickly out of late swing in an attempt to decelerating sagittal plane ankle motion into dorsiflexion, and block over-pronation and thus, more knee external rotation.

- Short, overworking tib ant: Concentric muscle tone. Some examples:

- Not being able to lengthen and load tib ant in sagittal and transverse plane in the previous phase of gait, propulsion, the tib ant will have to contract excessively on swing to dorsiflex the ankle to clear the ground (or turn the foot out).

- An externally rotated knee may be attached to a foot stuck in pronation and ankle stuck dorsiflexed, which will shorten tib ant in sagittal and transverse plane.

- If a high varus angle of the foot is present as an attempt to slow pronation and knee external rotation (as this increases the distance the 1st met must travel before it hits the ground), this will contract tib ant in frontal plane.

I’m sure this is not a complete list. I am, of yet, not sure which one of these is the most true for each of my three individuals, but what matters more than the story I choose is the “what will I do next”?

LOW FEMORAL-ACETABULAR EXTERNAL ROTATION

In order for this to make sense, we must distinguish between femoral rotation (FA: femur moving in acetabulum), acetabular-femoral rotation (AF: acetaculum moving on femur), and hip rotation (the orientation of the space between the two bones).

Until I understood this distinction, and a lot of it has to due with timing, hip mechanics fucked with my mind. I blame PRI. Just kidding… I blame my limited thinking, conditioned by previous PRI training.

Moving on!

Curiously, in all three individuals, the right hip- the same side as the externally rotated knee, was more limited into external rotation than their left. Why could this be? (and yes I am aware that this is a left AIC pattern…)

When the knee is externally rotated, the hip can be either internally rotated (IR) or externally rotated (XR), depending on which phase of gait we’re talking about.

There are two phases of gait in which the knee does XR: Suspension and early swing. Both are pronating, and knee bending phases. The distinction: In suspension (closed chain), the hip is in XR, while in early swing (open chain), the hip is moving into IR from maximum XR.

In either case, if you were to freeze time at the moment the knee is in XR, the hip would appear to be in XR as well. In one case because it is really truly in XR (suspension), in the other, because it is still in a state of XR but moving into IR (early swing).

PLOT TWIST: In suspension, though the hip and knee are in XR, the femur in the acetabulum itself in internally rotating.

How can an internally rotated femur be labelled as externally rotating hip?

Here’s how:

Suspension= FA IR + AF XR + (*some timing stuff*) = Hip XR.

Remember the femur and the hip are not the same thing. The femur is the bone, the hip joint is the space between the femoral head and the acetabulum.

*Aforementioned important timing stuff*: In suspension, the pelvis is rotating away from the suspending leg (AF XR) as, just prior to hitting the ground, the leg was in swing. The leg swinging rotates the pelvis away from the swing leg (creating AF XR), as the femur also rotates externally (FA XR). Then, as the first met hits the ground and foot starts pronation, the femur begins to rotate internally, initiated by the talus as the foot begins to pronate. However, the pelvis is still rotating away (into AF XR) faster and farther than the femur is rotating internally, which creates a global position of hip external rotation.

Clear as mud, right?

Early swing, by contrast, is simple:

Early swing= FA IR + AF IR = Hip IR

So, when the knee is in XR, the femur IS internally rotating regardless of what the hip is doing. When the knee is in XR, the femur is internally rotated farther that the tibia.

Knowing this, it makes sense to feel a limitation in femur XR on the side that has an externally rotated knee.

This also makes sense as a contributing factor to why propulsion wasn’t happening: In propulsion we need hip AND femur XR along with knee IR.

LIMITED RIGHT TRUNK ROTATION

Having an externally rotated right knee and limited right trunk rotation are not an absolute coupling, but it was curious to see it in all three individuals this week. It was pretty interesting example of the clever body making adaptations above to accommodate something below (or is it something below adjusting for a structure above…?)

In two of the three, the same situation was going on:

In gait, both had an observable left trunk rotation. Ribs were going left-center-left-center, and never making it to the right.

BUT, in a bilateral stance, the opposite showed up: Both had an inability to rotate to the LEFT. What the f***. I was not expecting that.

Why would someone rotate left so much while they walk, but not at all when isolating ribcage movement in bilateral stance?

My operating theory is, what if they were already rotated left, and in which case, there is nowhere else to go. You can try this in your own body. Stand with your shoulders rotated to the left. Now, try to rotate them more to the left. Doesn’t get you very far, does it?

So why would the body choose to put its thorax to the left, and how does this relate to a right externally rotated knee?

Remember, knee XR happens twice: Suspension, and early swing. In both those phases of gait, the spine and ribcage will be rotating, wait for it….

TO THE RIGHT (as per the Flow Motion Model™)

What if the body is avoiding right spine rotation because the knee is already in end range XR? More right trunk rotation would potentially require the knee to XR further, and that would probably not feel good on an already externally rotated knee.

We can look at it from another perspective. Maybe the left trunk rotation is what is trying to create right knee IR. In all (but one) phases of gait in which the right knee is in IR (transition, shift, and propulsion), the spine will rotate LEFT. (the exception is right heel strike, in which the trunk will be rotating to the right, even though the knee is in IR).

So, right trunk rotation couples more with right knee XR, and left trunk rotation couples more with right knee IR.

So which is it? Using left trunk rotation to attempt to IR the knee? Or avoiding right trunk rotation to protect the right knee from excess XR? The answer will be “both” until we know for sure.

In any case, working on reintroducing right trunk rotation and right knee IR will be a nourishing experience. Hopefully… (so far so good).

CONCLUSIONS?

Yeah, I guess I have a few.

- I’d better take care of my own right knee just in case I’m projecting my own problems onto people. Will put that on the to do list for today.

- Is this right knee external rotation a PRI pattern? Part of the lef AIC pattern?

- These three individual cases also had other different things going on. This is not the full picture and not meant to be taken as an absolute. I just like to write out my observations on the shit I see to make sense of it.

- Part of the solution for all three of these individuals was to work on “transition” (AiM movement) to experience knee IR. All reported that it felt “weird”, “good”, and “I never do that”. No shit you don’t!

- Knees are pretty cool. For a joint with only two planes of movement, amazing how overlooked its mechanics are. It only took me 4 times through AiM to start to get a grasp on the knee. Maybe after my 6th I’ll understand shoulders.

- This blog post is entirely a thought experiment. None of this may be true. Take it all with a grain of salt.