Before we start, no, this is not a post to put the B in BPS (bio-psycho-social) on a pedastle. The B could not exist without the PS, nor could we have a PS without a B. Such is the nature of all things that exist interdependently. I do not wish to engage in this debate. I also suck at debates…

Moving on!

Somewhere around year 2015 I’ve found myself in a bit of an existential crisis that I’m certain many other personal trainers have found themselves in at some point:

I LOVE WORKING WITH BODIES BUT I THINK THERE IS SOMETHING DEEPER I’D LIKE MY CLIENTS TO GET OUT OF EXERCISE AND THAT I’D LIKE TO ACCOMPLISH THAN COUNTING REPS.

Of course there’s more to being a trainer than leading mindless workouts and rep-counting. And I’ve never thought about my work to be limited to just that.

And as a personal trainer who does not claim to specialize in weight-loss or nutritional counselling or physique enhancement- typical things associated with my field, just what meaning does my work have?

WHY the heck am I doing this? Aren’t personal trainers supposed to help people lose weight and exercise and sweat and build muscles and all that stuff? And if I don’t place a priority on that stuff… Then what else do I bring to the table?

As I deepened my learning about the human body, began to observe what was really happening with the bodies of my clients, I began to see that strength training and “exercising” maybe wasn’t the thing they needed to prioritize.

When a client who had hip pain couldn’t do the usual “go-to” exercises, I found ways of working around the issue for as long as possible to deliver a pain-free workout, but this wasn’t enough. I wanted to have the information and abilities to address these issues with movement, not work around them with strengthening exercises that may end up more deeply ingraining their structural issues.

The more I learned and studied the human body and movement I began to view my work in a different light. Strength training and general “fitness” training lost it’s be-all-end-all power as the ultimate tool for helping people, and I realized that I needed to be doing more for the people who trusted me with their bodies than provide “exercise”.

I think other personal trainers have experienced a similar meaning-crisis, which may lead to 1) changing careers, 2) adding new skills to our arsenal and adapting the way we work and market ourselves, or 3) becoming disillusioned completely with our work and industry and lose all sense of meaning in it.

I am currently in the depths of situation #2 (only very briefly did I linger in #3….): Learning to integrate the skills I possess that go beyond strength and conditioning, re-positioning myself as a personal trainer who does more than lead “workouts”, into the realm of restoring optimal movement quality to support a wide variety of goals any client may have, from reducing pain symptoms, to optimizing physical and sports performance, to lifting heavy stuff because it feels empowering.

Today I would like to speak a bit more specifically about a fundamental piece of my operative philosophy that I find myself repeating as I learn to integrate the tools I possess: Investigating the bodies true priorities before deciding that strength will make things “better” (whatever our definition of “better” is).

As a personal trainer with understanding in both areas of strength training and biomechanics, how to balance these priorities? Is strength training with good technique enough to improve movement mechanics? Or will addressing biomechanics lead to improvements in strength that resistance training alone could not?

Obviously it’s not a “this over that” situation. It has to be both and all in any situation.

And HOW to achieve that balance is the tricky, variable bit, as no two people are the same.

Too, there is the issue of expectation and trust, when a client is looking for a type of training that validates what they perceive to be their specific limitations or goals, rather than seeking the truth of the issue, which may not be the same as how they perceive it. This is where client education, proper assessment are important, as is being able to meet the client where they’re at. If I give them something to do that is so far off the radar of their expectations, they will likely not appreciate it or see the value in it. This begs the question- do I give them what they need, or what they want?

Again, the answer is, BOTH! Always both. Finding the sweet spot for every individual. Meeting them where they’re at.

I think the art of “finding the sweet spot” is one I will be aiming to master for the rest of my life…

Finding the sweet spot

As we can all appreciate, in a holistic model of helping someone reach their goals, we have to take all aspects of “training” into consideration:

Restorative stuff: Yin (stuff having to do with homeostasis of all systems):

- Possessing ideal joint mechanics*

- Ideal breathing mechanics

- Sleep, nutrition, stress management, hydration, blah blah blah, for healthy organs and systems function

Exercise based stuff: Yang (training you do to push your body to do stuff harder, faster, better, etc):

- Strength and power training

- Aerobic/anaerobic exercise

- Skills/sports specific training

I would like to argue that biomechanics are like a mesh that surrounds and intertwines all aspects of the Yin and Yang of performance, health, and well-being.

For example, having ideal and efficient joint biomechanics (movement/posture) will help with breathing, reduce issues of compression on the organs, blood vessels, nerves, lymphatic system, etc, help the body stay pain free, enhance sleep, allows for proper digestion and elimination, and improves blood flow to distal body parts and the brain to enhance cognition and emotional regulation.

Having great biomechanics also spills over into all aspects of fitness and athletic development: the building blocks for producing force and power efficiently, and will impact on aerobic fitness by virtue of having mechanics in place for efficient breathing and economy of movement. Ideal biomechanics will lay the foundation for performing specific skills better, while also allowing an athlete to unwind from their repetitive specialized movements so they can get back to training the next day. Not to mention people with more efficient biomechanics will likely have less risk of injury and will take less time off training.

What do I mean by “better” biomechanics?

I’m talking about adult human gait mechanics of the Flow Motion Model as the “gold standard”.

Read more about that HERE. And HERE. And HERE.

Some may say that the “exercise stuff”- strength training with good technique, high quality technical skills work, will be enough to take care of the bio-mechanics bit in itself, and why spend time focusing on it?

“Squatting with ‘good’ form will keep you pain free”

“Animal Flow will fix your joint issues because it is ‘natural’, variable movement”

I agree to a certain extent, but disagree that people with real biomechanical anomalies will be “fixed” by good squat technique and simply getting “stronger”, or by pretending to be a monkey and crawling on the floor. (Note, I realllly love squats and crawling on the floor…)

Moving differently is great, but moving differently is still only a work-around for a specific issue or movement being avoided, whether conscious of it or not.

Yes, working specifically on changing the way people move and time their joint actions can be subtle, focus-demanding, tedious work, requiring daily practice, patience, and trust. Most meaningful work is…

That said, addressing biomechanics won’t automatically make you stronger. If coming from an untrained state, enhancing spine and shoulder mechanics, for example, will not miraculously bring you from zero push-ups to 5, just as if you are in pain, going from 0 to 5 push-ups may not reduce your symptoms.

Prioritizing…

Do you know your priorities? In your life? For your body?

Take a close look at what values, in the physical realm, are honestly important to you. Do you play a sport? Are you trying to maintain “fitness” as you age? Do you want to feel strong? Pain-free? For health enhancement and quality of life gainz?

Many people are unsure what they want out of a physical practice, and what they value in one. They may say they want one thing, like to be strong, or to be “in shape”, but don’t have a clear picture of what that means.

“Strength” might be a means to an end- Not the real value, but an expectation for a process.

Someone may perceive that exercise and strength training will make them pain free and perform better at their sport, and come in with an expectation that strength training, like they’ve read about on someone’s blog (not mine….), is what will get them to their REAL goal, which may have nothing to do with their level of strength.

I’ve been investigating what I truly value in a physical practice for the past several years, after my forced exit from the world of dance.

My primary value for my physical practice is to comfortably, confidently inhabit my body, at rest and in motion, and possess an awareness of it that allows me to heal myself when I get into trouble with it (which is inevitable).

What secondary values do I hold that bring my primary value to life?

- Strength. When I feel strong I feel more confident and comfortable in my body. My definition of “strong enough” is probably different than that of others. I have no desire to compete in a powerlifting competition, or be an elite athlete, but I enjoy the experience of being in my body more when I can do push-ups, chin-ups, squats, and deadlifts.

- Quality of movement. This is fundamental to strength development and so I prioritize my movement mechanics over getting strong. Can my joints do all the things their architecture was created for? I will not push my body in training beyond the point where my mechanics can take me.

Knowing my priorities now helps me to choose how to act according to my goals. As a dancer, my priorities were the inverse, and I was pretty depressed and in pain.

What if we don’t know what we really value? Or what if our perceived goals are not in alignment with what our bodies need? And what if our goals are not really our goals, but someone else’s goals for us? Then our approach to training will be off as well.

There has to be this sweet spot where our true values come together with where we’re currently at, and our method reflects and respects this. I think this space is met when we take the time to investigate what we really value, and is defined by acceptance, patience, and trust. A falling away of the ego and expectation for what we “should” be doing.

Maybe I’m getting a little philosophical now for a blog about biomechanics… But the method we follow matters little without investigation of the “why” behind it.

That’s what THIS tattoo is a reminder of…

So, that said, I want to share two stories from two different dancers and how they view their priorities, and their take on biomechanics vs. strength training.

Meet Sergio

I recently met up with a reader of my dance blog in real life- A dancer/musician visiting Toronto from Europe. I’ll call him Sergio.

We met up for coffee and he told me the story of his discovery of strength training and of how, inspired by Pavel Tsatsouline, the simple addition of squats and other basic strength training exercises into his gym routine boosted his dancing because he was able to move more efficiently. This is how he found my blog- searching for information on strength training for dance.

If basic strength training had these effects on his body, why couldn’t everyone have easy access to this simple performance enhancement method? A sentiment that resonates with me as well, and is why I got into this field in the first place, spending three years focused heavily on working with dancers. That’s why I wrote a book (<— available by donation right now!).

Sergio wondered why I care so much about getting into the nit picky details of movement mechanics when performance enhancement is so readily available to anyone who steps into a gym and picks up a weight and uses progressive overload.

Again, I don’t disagree with this. I’ve experienced this performance enhancement phenomenon it for myself, and many of my dance clients have, too. And, as my role as a personal trainer, people are neither expecting nor asking me to help them with specifics of joint biomechanics that they aren’t even aware are a thing to work on.

But to get someone to squat on their flat, pronated feet that don’t know how to supinate makes me feel ethically wrong, and sooner than later I feel obliged to shed light on the client’s limitation.

Yes, initially getting stronger will probably make that person feel better. But let’s go back to the squatting on pronated feet example.

25% of the bones in the body belong to your feet. If 25% of your bones are not moving in a full body loaded exercise, like a squat, for how long will squatting be the solution until it becomes a new problem? Something else is going to have to move to make up for 25% of your bones that aren’t moving. Will it show up in a few days? Maybe a few months? Years? I’m not willing to ignore that and wait with crossed fingers. (And yes, your foot bones should have some movement when you squat).

Where Sergio is at now, he is prioritizing strength training. Is that wrong? I don’t think so, because we don’t have enough information!

In Sergio’s credit, he is very body aware, and has a deep practice of inner investigation. He knows when something is not right for him and knows how to change when he’s stuck in a pattern that doesn’t serve him.

But while Sergio claims he has no current troubles with his body, what I think needs to be considered is what happens in 5 years if he keeps strengthening, reinforcing, his body with possible underlying movement issues that he is not aware of? After all, he IS a dancer, and I’ve never seen a dancer (or a human) who didn’t have some issues with their body.

I am a good example of how Sergio’s mindset started off great, and then went horribly wrong (or right… depending how you look at it).

I fucked up.

Here’s a story about me, because it’s my blog and I’ll write about myself when I please.

When I initially started strength training as a 20 years old dancer, I noticed right away that the extra work capacity that came from developing strength through squats, deadlifts, and push-ups had a dramatic change on my dancing. I felt like I’d struck gold. Found the “missing link”. My teachers noticed I was dancing “better” and I started getting all sorts of positive attention from them.

But what happened over the course of two years? I became over-trained (because I wasn’t planning my training schedule properly and was working out 4+ days per week on top of dancing everyday for hours), and I got injured (because no amount of squats or deadlifts in themselves could resolve the underlying postural and movement distortions my body had ingrained over the course of my life thus far).

What I needed was to address my movement mechanics to support my training, both in dance and at the gym, and in life (to get some healthy blood back into my brain, to be quite honest).

Applying myself to strength training was like fixing an atom bomb to my proximal hamstring- Using a potentially useful science in a destructive way.

Unfortunately, Google can’t assess your structure

Advice on how to address your specific movement mechanics is nearly impossible to search for online. (Maybe that’s why you’re reading this?)

This is because the same injury may manifest in X number of different outcomes and no two people will have the same experience of the same injury.

A fully “healed” ankle sprain may show up years later as a laterally flexed spine or a rotated pelvis or a knee that doesn’t extend. So one can’t just go online, type in “exercises to fix an ankle sprain“, or “exercises for my sore SIJ”, and find the solution. Because Google can’t assess that “why does my back hurt when I squat?” is a result of an ankle sprain five years ago that has now manifested itself as postural and movement distortions through the entire skeleton.

“I want to strengthen my ankles”

I will use another example of a young Highland dancer I did a few sessions with recently. We’ll call her Ally.

One of her primary goals was to improve her ankle strength to help her jumping. If you don’t know what Highland dancing is, it’s hardcore. You basically have to jump on one foot for 2 minutes straight without moving your upper body or putting your heels on the floor, all while looking pleasant.

Check it out:

I noted that one of the most important assets for a highland dancer would be the ability to create a rigid lever through the ankle, holding a supinated foot shape throughout the high volume of single leg hops they must do in their routines.

The foot creates it’s most supinated, rigid structure in the toe off phase of the gait cycle, and so for a highland dancer, being able to access the mechanics of this phase- foot supination, ankle plantarflexion, is crucial to carry over into their sport.

Crucial to this is also the ability to create a mobile, adaptive foot that can leave the rigid state when they are not dancing to allow for “normal” gait mechanics for proper recovery from training and performing. Too, the muscles of supination will only get their chance to load during pronation, and so to not access pronation limits access to supination as well.

We need both!

Too, a highland dancer would need the ability to generate power from their hips, especially since dorsiflexing the ankle is going to be limited due to not being able to put the heels down during their jumps. That said, the hips are also going to be limited in how much they can load and explode as the dancer must stay perfectly upright, limiting how much they can actually flex from the hip to generate power (glutes load in hip flexion). Much of the strength is really coming from a partial range of motion in the ankle, from partially plantar-flexed, to fully plantar flexed.

Like I said, it’s a hardcore dance form.

Getting back to Ally.

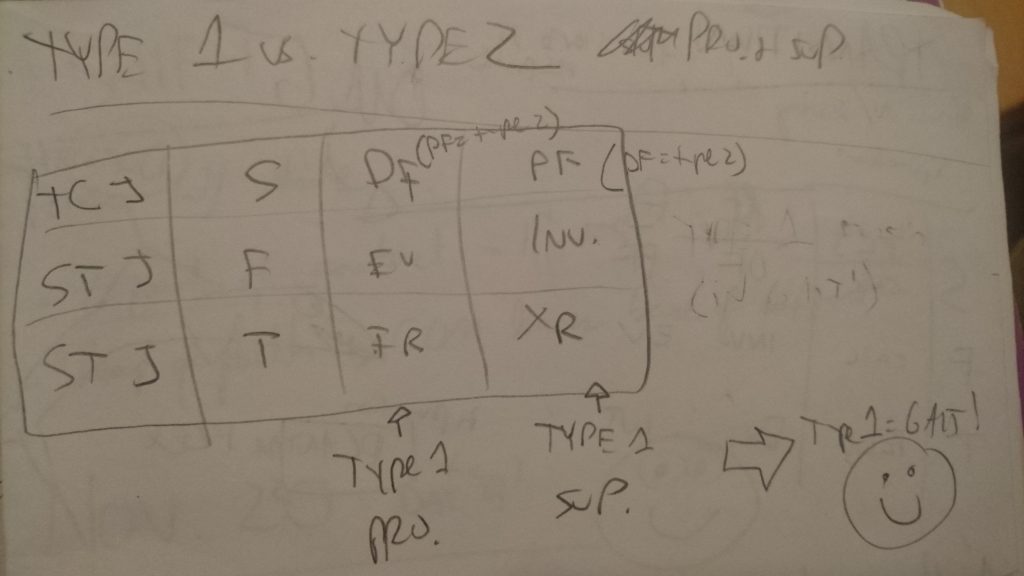

Ally already lifts weights. She can squat and deadlift more than most teenagers, and so she already has a base of strength to support her dancing. But are her biomechanics in place for her dancing to benefit from the stregnth training she is already doing?

As it turned out in our assessment, Ally could not supinate her feet- both feet were stuck pronated, ankles dorsiflexed, especially her right foot. Remember, in highland dance, being able to supinate the feet and plantarflex the ankles is kind of really important.

Her hips also did not flex. Instead of flexing her hips, her ankles dump into dorsiflexion and pronation, she posteriorally tilts her pelvis, and flexes her spine. This means she does not load her glutes when she jumps- They stay locked short.

This also shows up in how she deadlifts- Hips unable to flex, so she massively dorsiflexes her ankles and pronates her feet. Is the way she is currently deadlifting helping her dancing? Or reinforcing inefficient movement patterns that will ultimately limit how much she can progress in her dancing? I am leaning more towards the latter.

In Ally’s case, I would prioritize her movement mechanics initially over adding “ankle strengthening exercises” to her training program.

When Ally asks for “stronger ankles”, what her body is craving is feet and ankles that can supinate and plantarflex to create a rigid lever to jump on, and hips that can experience flexion to help her load her glutes and generate more power in her jumps.

In her dance training and working with her technique coaches she would want to slow down to integrate the new mechanics. For example, as we’ve been working on helping her train her demi-pointe with REAL supination mechanics in place (as opposed to type 2 pronation- ankle plantar flexion on a pronated foot), she may need to take a few steps back in her dance training to make sure she can better use these mechanics. A few steps consciously, patiently, back can lead to monumental progress forward.

In her cross training with weights, she would want to focus on integrating the changes in movement mechanics into her lifts. As we’ve been working on helping her get REAL hip flexion (instead of the exchange that is taking place at her ankles and spine) she may need to take the intensity back in her strength training to make sure she can access a proper hip hinge. All the hours of cross training she is doing with her cross fit workouts may not be to her benefit unless they are reinforcing useful mechanics.

CONCLUSIONS?

There is a balance to find. A sweet spot in training for any goal.

Does their goal truly reflect their priorities?

Is there necessary work to be done on basic on joint/movement mechanics?

How much technical skills training can their body take with the mechanics it currently has to work with?

What volume and intensity of strength training will enhance their performance without reinforcing old movement habits that are not useful?

And how to package this in a way that inspires trust in the process?

These questions haunt my dreams.

But this sweet spot is not a perfect 50/50, or 25/25/25/25. Balance may mean 75/25, or 80/20, and this depends on where you are now, where you’re coming from, and where you’re going. And the purpose of one’s training will never be fixed, but always changing, day to day, week to week.

As in Ally’s case, as highly trained Highland dancer who already has a solid base of strength, it is my view that addressing her joint mechanics will likely have the biggest impact on her performance goal, and this point in her training. For now.

In Sergio’s case, as a highly trained dancer with no current injuries, adding in something he didn’t have in his training-Strength development, made a radical difference in how his dancing felt. Ain’t nothing wrong with that. For now….

But for both, neither solution will last the course of time. Things always need to be reassessed and adjusted based on where the body is now.

When I was a hypervigilant, chronically-in-pain person, low threshold, restorative work helped me find balance. But then after a few years of that, to restore balance, I needed to also explore the other spectrum (which I did through Hardstyle kettlebell training).

It’s more a question of constantly asking and evaluating “What’s missing that is preventing me from doing what I do better”? Where are you not supported in your training? Where are you not supported in your life?