Have you heard of the “Leaning Tower of South Padre”?

Officially named Ocean Tower, the unfortunate story of this premium condo building can teach us a lot about having a sustainable movement practice. Like, one that doesn’t lead to self-destruction and cost millions of dollars.

Ocean Tower was supposed to be awesome. 31 stories high. A sweet view of the Gulf of Mexico. Complete with gym, pool, and spa. Each unit would sell for ~$2 million USD. Except for one teenie tniy issue…

The foundation was shite.

In 2008, two years after constructions began, the building started to sink and lean. The whole thing shifted more than a foot. The official explanation was that the parking garage and the tower were mistakenly built connected, forcing the weight down upon the garage instead of on the tower’s core walls. There was also something not quite right with the soil quality.

In 2009, Ocean Tower was demolished because fixing the foundation would have been too costly.

Many of us are like Ocean Tower.

How’s YOUR foundation?

Hello, I am the Leaning Tower of Monika (by Lake Ontario). Built in 1989 on a shoddy foundation that began to sink and shift significantly enough to require a massive, costly overhaul by 2012.

Fortunately unlike Ocean Tower, I don’t have to abandon the project and self-destruct. I can focus on rebuilding the foundation I never had.

And so can you. And I will argue that this is where most of us don’t spend enough time when we have problems with pain and performance.

What do I mean by foundation?

Check out this quick excerpt from my latest Liberated Body (part 2!) workshop:

Your foundation is made up of the most basic building blocks of movement we humans can do- must be able to do, for higher level activities. The individual joint motions that, when combined correctly, become the raw material for all other movement patterns.

How well-built is your foundation? Are you missing any building blocks?

I had some foundational issues from the start:

- I didn’t crawl (mom says I just wiggled “like a seal”)

- I stood up and walked before 12 months

- I hit my head a few times when I was very young

And those are only the things I KNOW about.

No crawling means my hip joints didn’t get to properly develop. In my infant body’s perception, I had a clump of feet-legs-pelvis-spine that couldn’t differentiate (kind of like Ocean Tower’s garage, mistakenly connected to the building’s core).

Standing up before 12 months isn’t an achievement. I didn’t “beat” the other babies in the standing race. Standing early is like ignoring Ocean Tower’s foundation problem, but saying, “fuck it, we can skip a few steps and get this tower up on time, it’ll probably be ok”.

Wrong.

And interestingly, skipping steps to get things done as fast as possible is kind of how I’ve lived my whole life. But that’s a tangent I won’t go down.

Are you searching for solutions for body problems, but feel like something’s missing? It might be something in your foundation, so basic it’s been overlooked.

Functional movement, strength training, and other modalities to educate our bodies how to “move better” and get out of pain might initially feel good. But for life-long sustainability, we need to know if we are missing any of our fundamental movement building blocks.

We all are. It’s just a matter of which ones.

Your Most Basic Movement Building Blocks

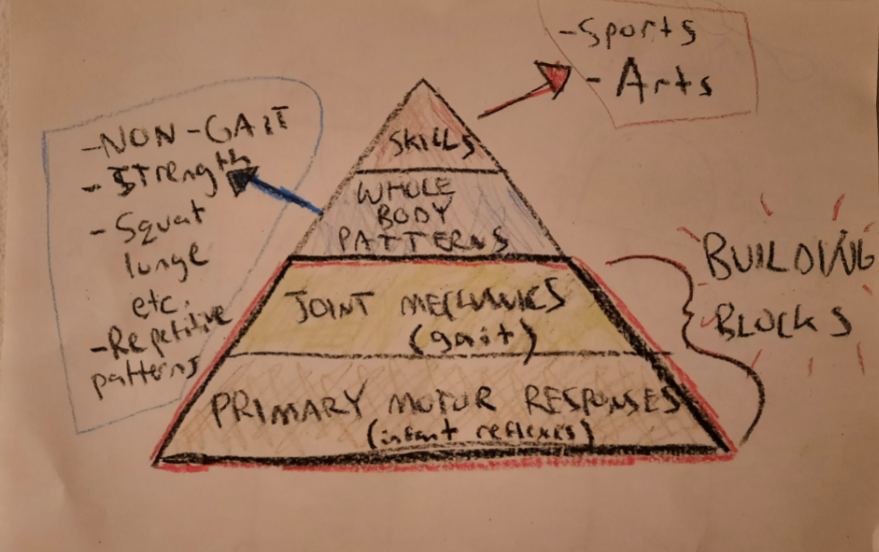

Do you like this drawing I made?

The lower two tiers are where I LOVE to play.

The building blocks: Primary motor responses (infant reflexes) and adult joint mechanics (upright gait).

When we get the foundation set right, everything above can fall into place with minimal effort.

Foundation level 1: Primary motor responses in utero

We start building our foundation from the moment we are a wee blob of cells implanted to mom’s uterine wall. Possibly even before that. And we don’t get much say in how this plays out.

In our cozy watery environment, we spend 9 months moving and developing our most basic joint motions. And it’s not random.

These building-blocks of movement are reflexive, pre-installed in our genetic code, and they serve to awaken the higher level “motor programming” needed for us to perform more advanced (but still basic) movements as infants, immediately after we are rudely evacuated into the “real”, air-based, gravity-ruled world.

But things can go wrong in utero.

You can be stuck onto the uterine wall weirdly.

Maybe there was a “kink” in your notochord.

Mom could have been really stressed, or sick, and it affected you.

Maybe you had a twin and one of you crowded the other, and maybe your right arm didn’t get to move as freely as your beloved sibling’s did because it was smushed against mom’s liver. That jerk. He became a baseball pro, and you failed gym class.

And then perhaps when you made your grand entrance into air-world it didn’t go so smoothly.

Maybe you were flipped upside-down. Your head got stuck under mom’s ribcage. They had to do a C-section. They tried to pull you out by your butt, but your head was reallllly stuck under there. So they had to pull harder and harder. Then you came out with a loud POP as your skull finally was liberated. How stressful! Good thing you can’t remember (imagine that happening to you as an adult…).

The above two stories are actually clients I’ve worked with. But their stories were unconsidered as being relevant to their problems with pain, posture, and performance.

Consider the movements we do in utero as building the first layer of our foundation. We have little control of this, so don’t dwell on it too much.

Just be aware that these foundational movements matter because they prepare us for the next phase: The primary motor responses we develop as infants for the next 3 years of life that helps us to develop our brains and bodies in tandem.

Foundation level 2: Infant reflexes

Between 0-3 years of age we develop the building-blocks for upright biomechanics: Walking. These are our primary, or infant reflexes.

There is a reflex hard-wired in our DNA to help us wiggle and bend and twist our spines to get down the birth canal (assuming we had that luxury).

To unfurl our spine from the comfort of the fetal position (assuming we spent enough time in fetal position in the first place).

To turn our heads, extend our arms and legs, discover we have a right and left side of our bodies.

To turn over on our bellies and learn to extend our spine and head up against gravity. What IS this gravity thing and why is it so damn heavy??

To push and pull with our arms and legs against the floor and develop our wee little hip joints (unless you’re me).

To discover we have this awesome things called a big toe, and we can push it into the floor to propel ourselves forward through space.

These events happen in a stereotypical way based on genetic programming that is similar for all humans.

And eventually we get enough building blocks in place, stacked together in the correct order, to stand up and start to walk.

But not all of us are so lucky, and going back to this level to give back the movements we are missing can be incredibly powerful.

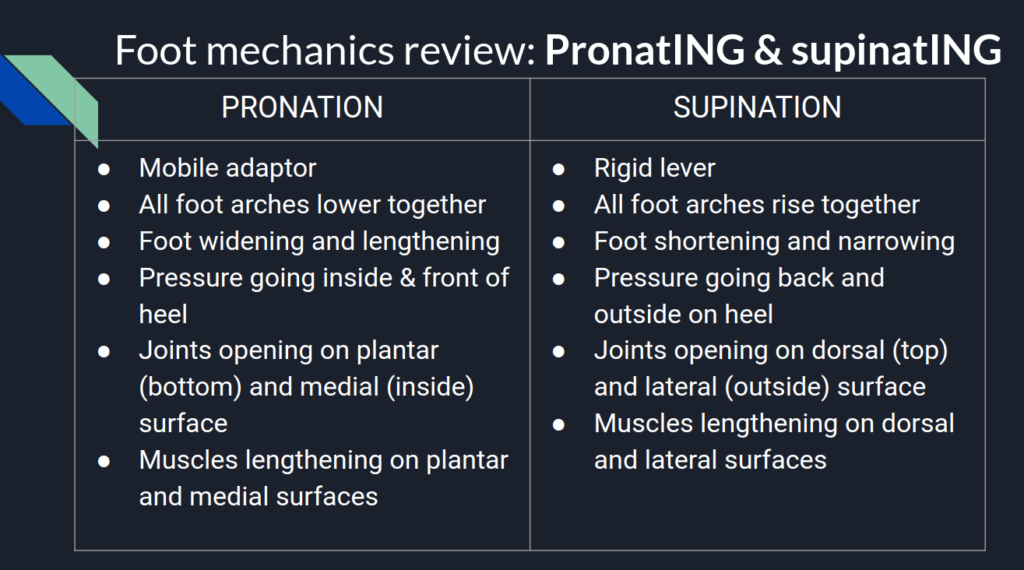

Foundation level three: Upright gait mechanics.

This is where, with gravity, we shape our muscles and bones by standing upright and bearing weight on two ludicrously tiny balancing blobs called feet.

In the gravitational field, we learn to flex and extend, rotate, and side-bend our hips, spine, arms, etc. And its not about strength- Its about discovering how our joints articulate when upright, loaded by our bodyweight, intending to move forward through space.

This is what Gary Ward has been mapping out in his Flow Motion Model and teaching in his Anatomy in Motion courses.

Its not a conscious process. Its more like a discovery of our musculoskeletal system and exploring what it can do.

However, even if we’re missing foundational building blocks, most of us still stand up and walk, and play, and exercise. And then we have accidents, injuries, and do things that distort how we’re able to move. As we age, entrpopy increases, and more building blocks go missing or put in the wrong place.

Where are the gaps in your movement foundation?

Our foundation for all movement is built on unconscious motor programming. And each level contributes to the next. And we shouldn’t skip any steps, but most of us do.

And good thing its an unconsious process. Imagine having to decide for yourself at one year old the “best” way to develop your body to walk? Imagine a one year old with the blueprint for Ocean Tower… Yikes.

You are probably missing a few important building blocks. How do we find which ones are missing and get them back? It will be super specific to your unique experience. This is why I am always hesitatnt to give specific exercises in these blog posts. Get assessed, don’t guess.

But you can consider questions like:

Did you crawl?

Did you stand up before 12 months old?

Did you have an interesting or challenging birth experience? (as the birther, or the birthee)

Did you have a stay in the NICU, pinned down with machines and tubes that kept you alive, but prevented movement?

Did you start a highly skilled movement form before 3 years old? (like all you dancers who started ballet when you were 2, I’m looking at YOU)

Did you have an injury or accident, especially before age 7, but at any age, that caused you to be immobilized, or altered how you moved, for a period of time? Like a broken arm or ankle, head accident, or illness.

Every insult to the body will cause a change somewhere. And if you change one thing, everything else has to change to accommdate that. That’s balance. Its not ideal, but it is “functional”.

We can get our foundation back by re-educating our bodies and moving with awareness, with a little guidance from someone you trust.

Awareness is hard

Knowing what your body can’t do is hard, but cause you don’t know about it yet… If you were already conscious of what you can’t do you probably wouldn’t have any problems.

The more I explore movement, the more I realize that the most value comes from re-visting the basics in more depth. Smaller, softer, subtler, more refined. Not bigger, harder, with more muscular effort and control.

When we move big and effortfully, we only reinforce what we can already do. This is why skipping ahead to strength training when things feel “off” or painful doesn’t solve an issue long term. It will not be sustainable unless your foundation is addressed.

Don’t be Ocean Tower.

Heavy deadlifts didn’t restore my shaky foundation. That only perpetuated my structure to lean and shift, like Ocean Tower, the taller it got, the shiftier it got.

When you can identify what’s missing from your foundation, and give those elements back, all your favourite higher level movements and activities become more natural and effortless, because more of your body is accessible to you.

And then, like me, you might realize that you don’t actually want to powerlift, because that “solution” was a lot of effort and kind of boring anyway. We get to ask the question, “Now that I have a foundation, what do I actually want to do with it?“. Your journey will be your own, and it may not be what you think.

And if any of that resonates with you, and you’re trying to “fix” your basic movement limitations with higher level activities, I encourage you to take a few steps back and see what could be missing from your foundation.

How to start rebuilding your foundation

Curious about what exactly I mean by “building blocks” of movement?

As I already mentioned, this will be a unique journey. You may wish to find a movement/therapy professional to assess and guide you through it.

As a general jumping off point, Gary Ward has created a few excellent online courses that may be of interest to investigate your upright joint mechanics and find what’s missing: Wake Your Body Up, and Wake Your Feet Up.

My workshop, Liberated Body, also helps you identify missing joint motions and coordinations that we need for upright gait (I teach it both online and in-person).

LB Part one is all about the level of gait mechanics: How should our bodies ideally organize for effortless, efficient gait?

LB Part two is a level deeper: How to explore the building blocks that preceeded upright gait- the primary motor responses, and then put those together in a meaningful way for effortless, efficient gait?

Liberated Body is available anytime as a home-study workshop. Part two must be done live, because I customize it to the individuals in the group, and work with you one on one to restore your foundation.

CONCLUSIONS?

Don’t be like Ocean Tower.

Its never too late to build your foundation.

I didn’t get mine right the first time, and exploring my missing building blocks continues to be an enriching part of my daily movement practice, and my life.

Reach out if you have any questions 🙂