December 18th was this month’s edition of the Movement Nerd Hangout: A free monthly session to welcome you into my wee community of self-professed movement detectives (aka movement nerds).

This month’s topic was Core Training From the Inside Out (part 1). I figured everyone’s thinking about their mid-section around this hedonic time of year, so yes I jumped on that marketing train. Sue me.

Over 100 lovely people signed up to explore some rather unconventional concepts and ways of experiencing their “core”, such as:

- What is core mobility vs. core stability? (and why this may be the missing link to building a strong core)

- How could ankle sprain rehab be considered “indirect” core training?

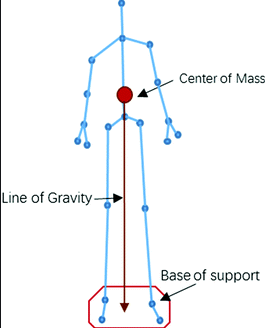

- What’s your center of mass (CoM) awareness got to do with core training? And how is it more important than a “neutral” spine?

- What the heck is “neutral spine” anyway? Should you work on it?

- How does Gary Ward’s rule of motion: Muscles lengthen before they contract, come to life in a diaphragmatic breath, as it relates to training dem abz?

- How does access to 3D spinal mobility actually improve core stability?

And more…

In case you missed the live session, here’s the complete recording:

Carve yourself out an hour to hang out with me and dive into my first two pillars of core training. Let me know how it goes for you!

And now, here’s the session breakdown, if you just want to read some words, or don’t have time to participate right now.

Core intentions

Here is what I set out to cover in the session:

- Understand what is “the core”? And identify the key anatomy.

- Understand and explore my first 2 (of four) pillars (that I made up) of core training: 1) Diaphragmatic breathing at rest, and 2) Accessing 3D spinal motion.

- Apply Gary Ward’s two rules of motion: 1 ) Joints act, muscles react, and 2) Muscles lengthen before they contract, to core training, in contrast to “core stability”

Whoah what? A core training session that’s NOT about creating stability and engaging your abs?? But isn’t the core supposed to be stable??

We’ll get right into that, but let’s first look at some of the key anatomy.

Core anatomy

What is the core, anyway?

In the session, I asked participants: “Point to your core”.

Do it now… What are you actually pointing to?

Are you pointing to muscles? Are you pointing to your ribcage? Are you pointing to your intra-abdominal pressure? Are you poining to your center of mass? Are you pointing to your breath?

The core is all of that, and more than all that. It is how all of that interacts.

The core is more than a set of muscles.

More than a label of weak or strong. More than something to squeeze, tighten, and brace. It’s more than stabilizing your spine. More than something to tone and make look good. And not something we need to dedicate a whole gym day to.

But I digress… Let’s take a look at the key muscles, bones, and joints of the core.

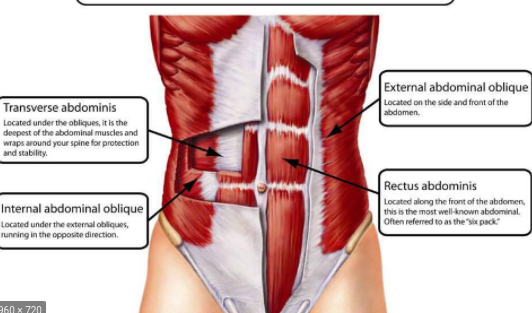

Key muscles & structures

Bones and joints:

- Pelvis

- Ribcage

- Spine

Muscles (that connect directly to those bones and joints)

- Rectus abdominis

- Internal obliques

- External obliques

- Transversus abdominis

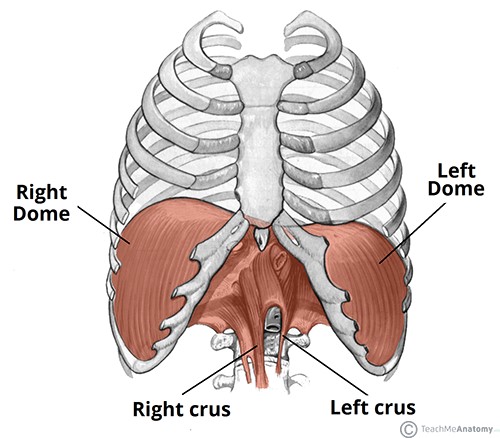

- Diaphragm

- Multifidus and other inter-vertebral muscles

*Note, however, we won’t be talking specifically about muscles today, because it’s actually not that useful experientially, and makes things way more complicated than necessary.

These structures and muscles all have a specific role in gait.

What does the core do while you’re walking?

WHEN does it contract? HOW does it contract? Should you even think about contracting it while you walk? (No…)

The abdominal muscles are no different than any other muscle in motion: They go through phases of loading/contraction, lengthening/shortening, as the joints they attach to go through phases of opening/closing, compression/decompression.

This all happens multiple times per foot step, in all three planes of motion.

While I don’t say it explicitly, day one of my Liberated Body workshop (spine mechanics day) could be considered a “core training” session, because it’s all about experiencing spine, pelvis, and ribcage movements as they occur harmoniously in gait.

Within the fraction of a second it takes for each foot step, all the structures of the core lengthen then contract, compress then decompress, in all three planes.

Gait might be the best core “workout” you can get 😉

So… Can you appreciate that core training is about more than just stability, six packs, and neutral spine?

“Direct” and “indirect” core training

This is something I made up, so take it with a grain of salt. But I’d love to hear if it resonates with you as a concept.

I’d like to poropose two types of “core training” (neither of which involves stability, or romanticizing neutral spine):

Direct (or local)

– Working directly with the spine and trunk musculature, the position/movement of spine, pelvis, and ribcage, and the ability to breathe within all options for those positions/movements.

– The potential for the structures named above to alternate between demands for movement or creating stiffness, in a way that is effective for the current task.

Examples of direct core training: Working directly on spine mobility. Doing core stability exercises, like deadbugs. In real life, being able to brace the abdominal muscles, create a rigid spine, and maintain intra-abdominal pressure in order to push your car uphill.

Indirect (or global)

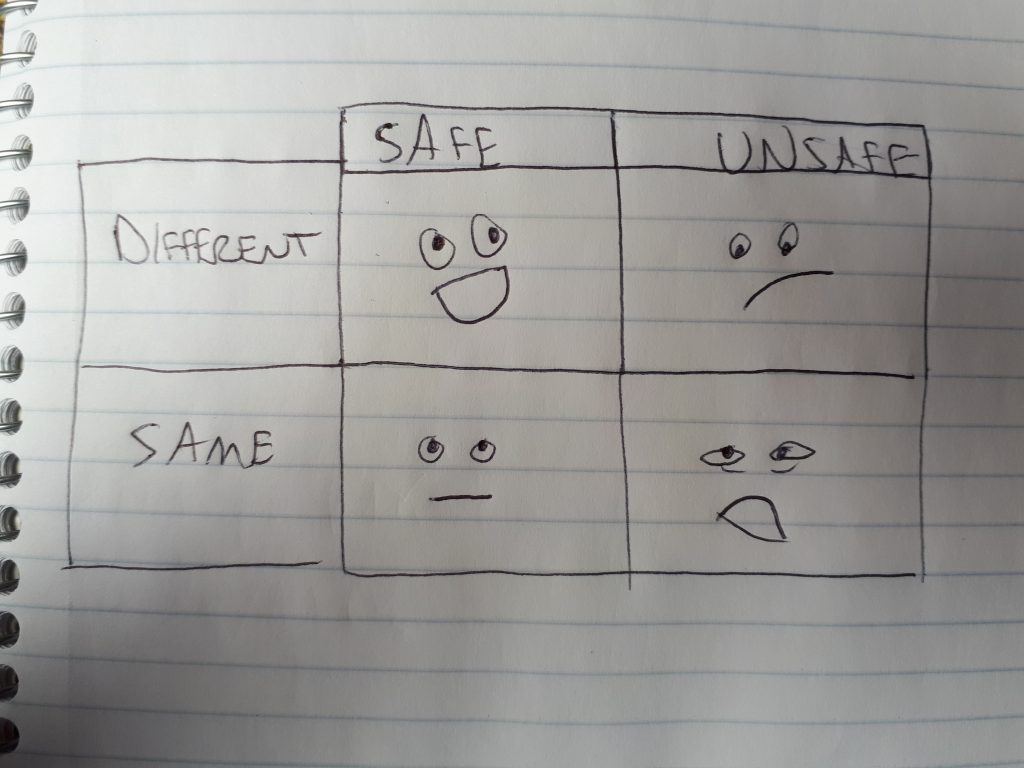

– Freedom for one’s center of mass (CoM) to move freely within the base of support of your feet, to all it’s edges. The ability to find your best “center”, having explored those edges, instead of forcing an idea of neutral spine on a structure lacking awareness of center.

– CoM mobility (or “core mobility”, a term Gary Ward coined in What the Foot) gives rise to the core musculature (and all musculature) reflexively responding, unconsciously, as the body moves.

– Indirect training is specific to the individual based on their unique history- Injuries, sports, habitual patterning and postures. Indirect work is to give the whole body back “what’s missing”, knowing it will impact on how the core functions.

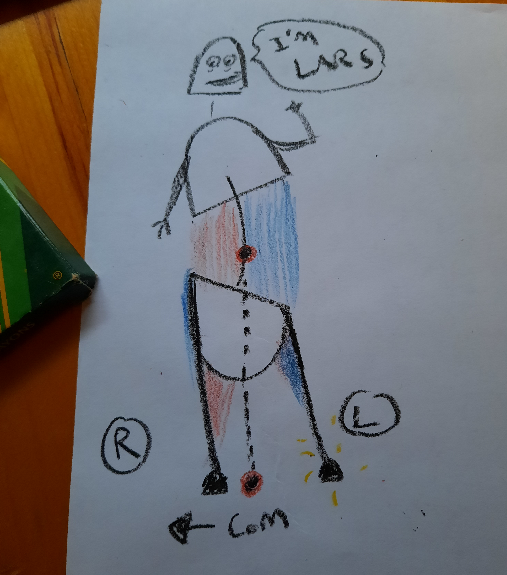

Example of indirect core training: I’ll use an example of one of my clients. I’ll call him Lars.

Lars had a left ankle sprain, and now he can’t bend that knee very deeply, and he can’t get his body (CoM) over to his left foot.

He looks a little like this:

Lars has left side SI joint and lower back pain, and does a ton of core stability training, because shouldn’t stronger abs help with your SIJ and back?

Not if the problem is that you can’t put weight on your left foot, which is the case for Lars. He can’t shift his center of mass left without weird compensations in his spine and pelvis.

All the blue shading is where muscles are getting pulled long, which are the areas he feels “tight”.

He is very good at training his abs in his off-center place- He’s got a very “strong” core. But it is not helping him to liberate his mass to move freely from one foot to the other, only serving to further lock him into an off-center structure.

As we’ve been working on his left ankle and knee, his pelvis and spine are balancing out, helping him to use his abs better, from a more centered place, because he doesn’t need to lean away from his left leg so much.

So yes, core training is absolutely about the spine, and muscles (direct).

And its also about the whole body’s ability to move freely, not avoid motions that feel unsafe due to past injuries, accidents, or trained movement patterns.

Lars’ ankle and knee movement training was indirectly giving him better access to his core, as he began to inhabit a more centered structure.

Ok now finally onto pillar #1…

Core Training Pillar #1: Diaphragmatic breathing at rest

This is my first “pillar” of core because a good quality diaphragmatic breath:

- Descends the diaphragm, smooshing down on your guts, which is necessary to generate intra-abdominal pressure so you can be strong AF when the demand arises (pillar 3)

- Mobilizes the spine, pelvis and ribcage (pillar 2)

- Lengthens all the abdominal muscles- A good indicator of their ability to then reflexively contract (Gary Ward’s rule: muscles lengthen before they contract)

- Has implications for many, many physiological, neural, and esoteric things that are fascinating but beyond the scope of “core”

I really enjoy this animation of the biomechanics of the diaphragm, and the effect of diaphragmatic breathing on the whole body:

To make things very, very simple, in the session I demonstrated a 5 quadrant quick check for your quality of diaphragmtic breathing:

- Sternum and belly anterior (aka apical) expansion

- Lower pelvis anterior expansion

- Upper chest (aka pump handle ) expansion

- Lateral ribcage (aka bucket handle) expansion

- Posterior ribcage expansion

Are you able to access all 5? Are you all belly and no pump handle? Or are you like me and your left ribcage bucket handle never moves?

All 5 quadrants expanding simultaneously, effortlessly, and unconsiously is a good indicator of a quality diaphragmatic breath.

Core Training Pillar #2: Access to 3D spinal motion

First remember: Core training isn’t just about stabilizing and neutralizing the spine.

Second remember: Your spine moves when you walk (well it should, but maybe yours doesn’t… yet!.)

Third remember: Muscles lengthen before they contract.

Fourth remember: Joints act, muscles react.

So as a prerequisite to having abs that can contract and create stability, we need access to the specific 3D spinal motions that occur with each foot step you take:

Sagittal plane: Flexion and extension.

Frontal plane: Lateral flexions left and right.

Transverse plane: Rotations left and right.

In the session we covered a few exercises to experience the sagittal plane motions: Flexion and extension of the spine. And as a bonus we layered on the 5 quadrant breathing.

Greater access to the whole spine’s movement potential acctually gives you greater ability to stabilize it, too.

To help participants experience this, I had them test out a plank (holding for ~5 breaths), and gauge how “stable” they felt.

Then after exploring some spine motions, I had them re-test their plank. Here are some of their reactions:

“2nd time felt much stronger, more stable and able to access my breath more fully”

“Foot pressure balanced out – started really far on the left foot – more balanced. Also much more stable plank :)”

Pretty cool, eh?

Conclusions?

“Core” can mean a lot of things. What does core mean to you?

Many folks start core strengthening and stability training from the “outside in”, before considering the “inside” part: Breathing, spine motion, and center of mass mobility.

Ankle sprain rehab can be considered “indirect” core training, because it can give you greater access to move evenly between your two feet, aka “core mobility”, or “finding center”.

Neutral spine only lasts a fraction of a second when we walk- A fleeting moment in time.

Diaphragmatic breathing is not belly breathing- There are four other quadrants that need to expand with the belly with every inhalation. How’s yours doing?

Giving the abominal muscles the experience of how they actually lengthen and contract as we walk, by accessing three dimensional spine motion, should be the first poriority for core training, before training for stability.

Want to tune in live for part 2?

Save the date: Wed Jan 27th 2021 @ 10:30am EST (Torono)

In Core Training From the Inside Out )Part 2) we’ll review the first two pillars, and dive into 3 and 4:

- Creating intra-abdominal pressure

- Creating spine stiffness with limb movement

Concurrently to this story about L, I was reading John Upledger’s The Inner Physician and You in preparation for taking the Upledger Institute’s craniosacral therapy level one course (stoked!). Reading this book was fortuitously timed, as I began to observe some of its main themes surface in my bodywork practice. In particular while working with L last week.

Concurrently to this story about L, I was reading John Upledger’s The Inner Physician and You in preparation for taking the Upledger Institute’s craniosacral therapy level one course (stoked!). Reading this book was fortuitously timed, as I began to observe some of its main themes surface in my bodywork practice. In particular while working with L last week.

In the book Don’t Sleep There Are Snakes, Daniel Everett tells a story of how the remote Amazonian tribe he is living with, the Pirahã, do not use numbers or math. He tried to teach them simple addition, but they didn’t have any prior experience with the concept of numbers or adding and would not learn. What if for some people, areas of their bodies feel like math did to the Pirahã? They could learn math if they wanted to, they have the same brains as every other human, after all. But they have survived so long without it, found a way of living without math, why start now?

In the book Don’t Sleep There Are Snakes, Daniel Everett tells a story of how the remote Amazonian tribe he is living with, the Pirahã, do not use numbers or math. He tried to teach them simple addition, but they didn’t have any prior experience with the concept of numbers or adding and would not learn. What if for some people, areas of their bodies feel like math did to the Pirahã? They could learn math if they wanted to, they have the same brains as every other human, after all. But they have survived so long without it, found a way of living without math, why start now?