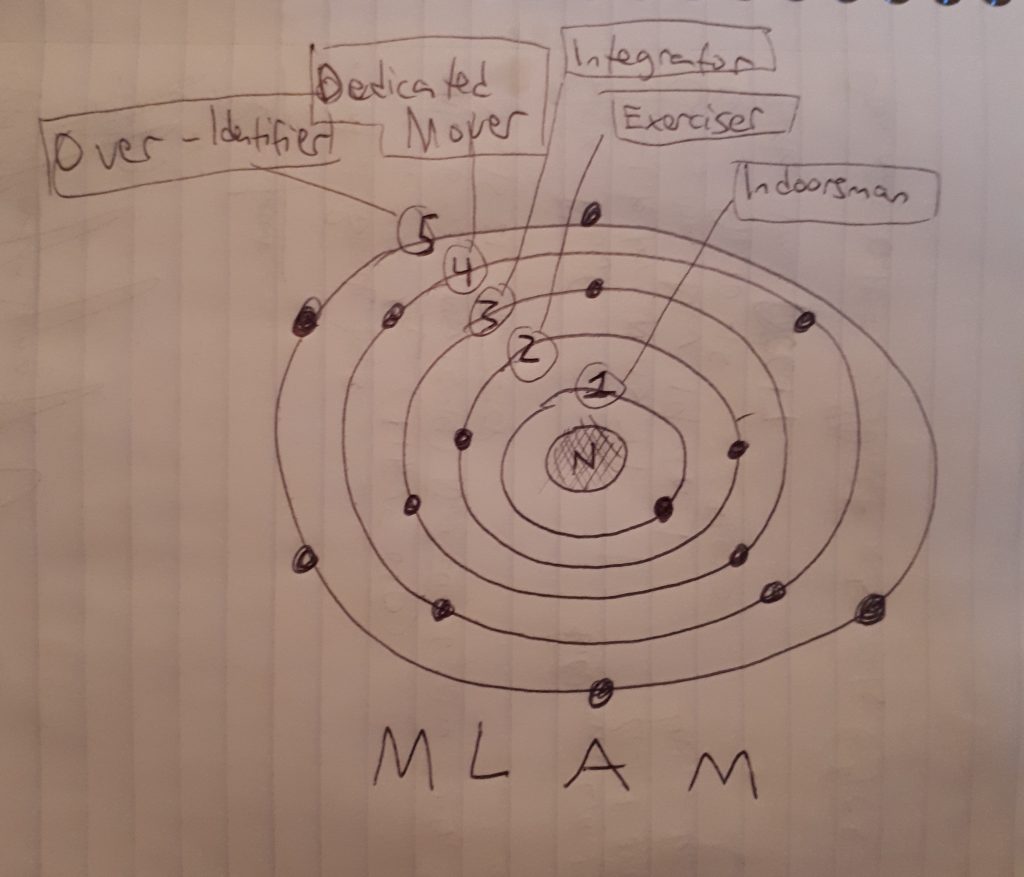

Welcome back. In part 2 we discussed some wacky ideas about atoms and electrons and archetypes and the MLAM (Movement-Lifestyle Atomic-Model).

If you’re still into this exploration of the implications of how we interact with movement in our lives (hope you are…), in today’s Movement Practice installment I’d like to discuss the third archetype who sits at the center of the MLAM: The Integrator.

Ready?

But first… An important message about this archetype thing:

Its Not Your Fate

You may find you resonate completely with the description of one of these archetypes I’ve described so far, or that you are a blend of several. An Indoorsman/Exerciser. An Integrator/Exerciser. I personally have been a little bit of each at different points in my life (save for the Indoorsman, thanks to the example set by my parents, I was brought up with an intrinsic value for movement, even if it became very unhealthy in my Over-Identifier days. Nor do I feel as if I’ve attained Transcender status, though I know of few of these individuals, and they are an inspiration to be around, providing an example for how to live harmoniously attuned to one’s body and environment).

These archetypes are only stories. Something I made up to illustrate a point.

In the chance that you might identify strongly with one of these archetypes, I’d like you to remember that while the characteristics of one or more of the archetypes may describe you right now, they do not define who you are and how you will always be. If you feel the Indoorsman is representative of you, with a lacing of The Exerciser, you are not doomed to be these traits.

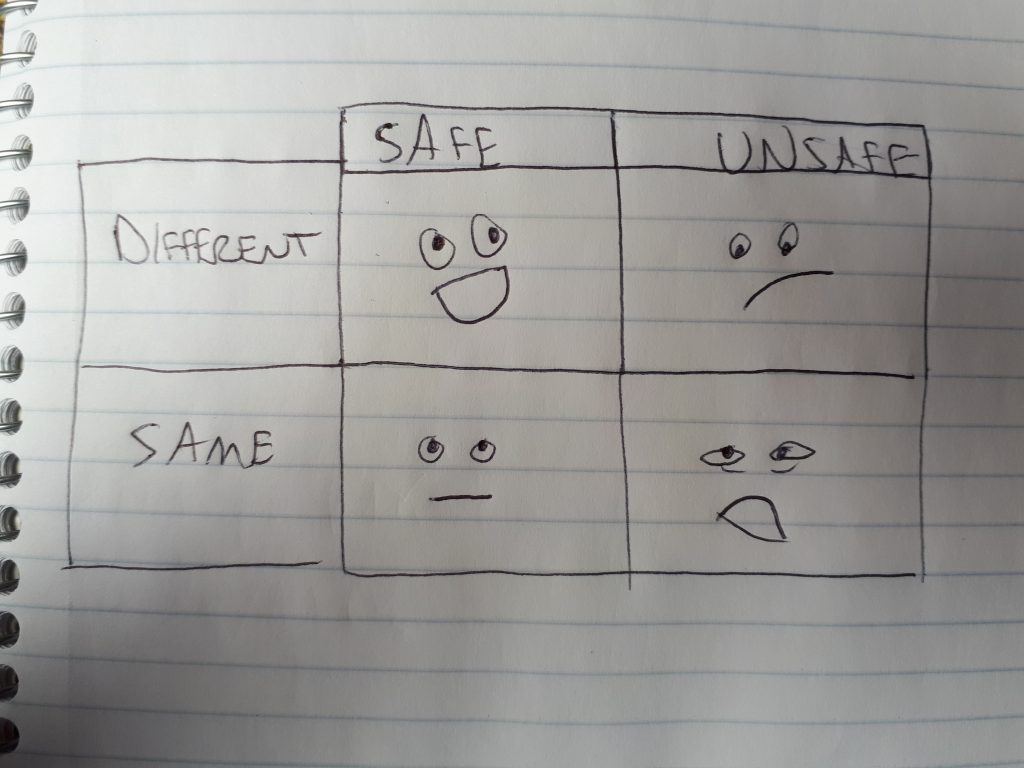

People can and do change all the time but this change does not take place without first asking the questions: Where am I now, how did I get here, and what what realm exists beyond my awareness? The difficulties in change arise in the inexorability of self-reflection and unpleasantness. It is step that most of us avoid, skipping ahead to the “here’s how to be the best you” step: The Indoorsman joining a basketball league without appraising that his health and fitness is nowhere near sufficient for this demand, for example.

By creating a caricature of the traits that you may not be willing or able to look at in yourself because they are too close, too deeply ingrained as patterns, the archetype descriptions can help you to zoom out and identify areas of your relationship with movement that you’d like to change. Stories can be powerful meaning conveying machines, but they are just stories. Our species has using stories since the earliest forms of pre-spoken-language communication to help to convey ideas in ways that conceptualizing and intellectualizing alone cannot.

My hope is that you do see yourself in one or several of these archetypes, but only so that you can get a broader context for the journey forwards as we explore your relationship with movement and how it may be impacting on your life, for better or worse.

What should interest you most is not which archetype you identify with, but the acknowledgement that the journey from shell to shell of the MLAM is what makes up the bulk of our lives, and instead of moaning about where we’re at now, we can ask, “How do I want to show up for this journey?”

With awareness, an explorative mindset, seeing our failures as opportunities to change? Or regret, disappointment, and frustration that you are who you are.

You are not any one archetype, inside all of us is the possibility of Transcender (an archetype we will meet a little later on).

Public service announcement complete, let’s meet The Integrator.

Shell 3: The Integrator

Dynamic and adaptive (in life and in his body), The Integrator possesses a certain je-ne-sais-quoi. You probably know quite a few Integrators who don’t realize they’re Integrators. Let’s demystify what makes this archetype distinct.

Professionally, an Integrator is 40% likely to have a job related to movement and fitness, such as a yoga teacher, sports coach, or massage therapist. There is a 35% chance that his job has a definite degree of physical demand such as being a bike courier, a walking tour guide, or a landscaper. There is a 25% chance that he has a low-movement, indoor, corporate, or office-type job such as a software developer, an investor, or an office manager. The common identifier of these Integrators of various professions and life-paths is that movement and being outdoors are one of their top three values, if not number one.

The Integrator can likely be spotted working out at the gym, but is equally likely not to have a regular indoor gym routine. More than the act of showing up to the physical location, he shows up to spend time in his body. He makes time for movement and activity as an integral part of his life versus seeing it as something to fit in amongst a plethora of other higher priority activities.

His movement practice is a cornucopia of movement forms, exercises, sports, and non-exercise activities that, when habitually engaged with, make him feel subjectively “good”. He has discovered, likely quite early on, that life is much preferable when h:e integrates movement into it (hence his name).

For him, “movement practice” exists on a spectrum with three landmarks:

1. Organized routines and structured practice.

2. practical movement integrations and non-exercise activities.

3. Spontaneous, creative, or improvised movement forms.

The most healthy, integrative integrator has aspects of all three landmarks in his practice, which I call possessing the Movement Practice Trifecta (MPT).

For example, The Integrator who has a fully established MPT may participate in, as his chosen organized movement practice (landmark one), powerlifting, Ashtanga yoga, or karate- Highly structured activities he wants to get better at and see progression physically. As his non-exercise activity (landmark two) he makes time for a walk outdoors at lunch time, and enjoys gardening in his leisure time. And as his creative, spontaneous movement option (landmark three) he may practice contact improv, or the flowing, creative work of Ido Portal, as well as engaging with the unplanned spontaneity implicit in playing a recreational sport.

Not all Integrators engage with the full MPT, and this does not make one Integrator better or worse, just at different points along the spectrum. You may recognize an Integrator as a doctor who plays in a ball hockey league, commutes on his bike to the hospital, and works out at the gym two times per week. You may know a CEO who’s alter-ego is a martial-artist and high level ping-pong player who is also practices carpentry on the weekend. Or you may know a chiropractor who is a StrongFirst kettle bell instructor, who plays with his dog at the dog park regularly, and plays beach volleyball on Sundays.

Many Integrators who are new to integrating do not yet have a trifecta in place, but are likely to have hobbies that can be done outdoors. If the newly anointed Integrator does not yet have a distinct structured practice, play a sport, or go to the gym, he probably has high non-exercise activity levels, as he organizes his life around his value for being outdoors and using his body in some useful, enjoyable way, such as hunting, fishing, carpentry, camping, playing with his kids and/or pets. He can’t imagine a life spent sedentary without movement or play.

Even though his day may be busy with appointments, meetings, or deadlines, he looks at his schedule weekly and makes time to move, treating these times as important appointments with himself. His priority is on weaving movement into his lifestyle. The activities that bring him the most joy and allow him to connect with his friends and family are movement based- He’d rather plan a social gathering around an afternoon gardening outdoors than sitting in a cafe; a camping trip over a gambling trip to Vegas, or a cycle tour of Vietnam over a luxury cruise in the Caribbean.

The Integrators who do have a structured training or gym routine approach it in a different way from The Exerciser. Their intention is less one of end-gaining and more about the process he engages in. It is less striving to be something he’s not, and more based on accepting who he is now, and who he chooses to be as he walks his path. Even as a powerlifter or other metric-based athlete, he is not attached to chasing numbers as a predictor of his success, and simply enjoys the journey he is on- The ups and downs, while aiming for his goals (and due to his process-oriented outlook, he often achieves his goals).

The goal of the Integrator’s training routine is to support his body so he can keep enjoying his favourite activities without omni-present niggling joint aches common to The Exerciser, and normal for The Indoorsman. He takes care of himself so that he can live the life he loves without fear of becoming injured or not being able to keep up. If he loves to hike with his wife in the wilderness, his practice of movement and strength training is geared towards helping his joints to feel healthy and happy so he can continue to do this for as long as he can.

Movement is integrated into his life, be it professionally, socially, or for personal enjoyment and health, and this contributes to his high adaptability to life’s demands. He bikes or walks to commute because it is empowering, economical, enjoyable, and as a bonus, good for his health. He values looking fit and healthy (let’s be honest, we all want to look good) but also truly enjoys working on new movement skills and trying new activities, finding himself looking forward to the peace and clarity that comes with deep practice and entering a flow state. He goes for daily walks not because the doctor told him he should exercise more, but because he knows he feels better when he gets more blood flowing to his brain and body, impacting on his abilities in his mental and professional areas of life. Because of this extra kick of blood to his brain, the production of neurotransmitters unknown to the sedentary, combined with a less chronically sympathetic nervous system state, he is also likely to be a better learner than the average human, seen as more intelligent, having more resources made available for his brain to use for something other than surviving.

His adaptability and vitality earn him his place on the middle shell of MLAM: He is resilient to mental and physical health risks, and his salubrious habits perpetuate a positive feedback loop, further contributing to his resilience. The key factors that distinguish The Integrator from The Exerciser is his moderate attitude, which sounds boring, but because of which we can account for his physical and emotional ease. Whereas The Exerciser fluctuates between highs and lows in her physical practice and mental state, The Integrator is level, enjoying a sense of inner peace and calm that the Exerciser does not, which inevitably trickles into other areas of his life, making him an excellent role model for us all.

The Integrator at a glance:

Superpower: Level-headedness, learning, adaptability.

Kryptonite: Inability to engage in a consistent routine, forced to sit for too long.

Vitality: Good energy, immune system, resilient to illness.

Relationship with movement: Integrated, balanced, trifecta.

Attitude towards the stairs: Takes the stairs because he has legs that work and doesn’t take them for granted.

Having fun with this yet? Whatever, I am. In our next Installment of Movement Practice we will meet our two professional athlete archetypes: The Dedicated Mover and The Over-Identifier. Stay tuned! If you really want me to let you know when I have some new writing to share, let me know. I can put you on my “People who actually read what Monika writes” gmail list.

Concurrently to this story about L, I was reading John Upledger’s The Inner Physician and You in preparation for taking the Upledger Institute’s craniosacral therapy level one course (stoked!). Reading this book was fortuitously timed, as I began to observe some of its main themes surface in my bodywork practice. In particular while working with L last week.

Concurrently to this story about L, I was reading John Upledger’s The Inner Physician and You in preparation for taking the Upledger Institute’s craniosacral therapy level one course (stoked!). Reading this book was fortuitously timed, as I began to observe some of its main themes surface in my bodywork practice. In particular while working with L last week.

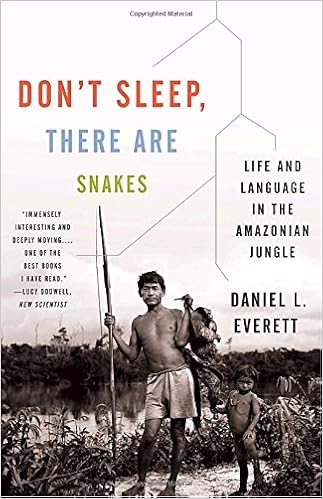

In the book Don’t Sleep There Are Snakes, Daniel Everett tells a story of how the remote Amazonian tribe he is living with, the Pirahã, do not use numbers or math. He tried to teach them simple addition, but they didn’t have any prior experience with the concept of numbers or adding and would not learn. What if for some people, areas of their bodies feel like math did to the Pirahã? They could learn math if they wanted to, they have the same brains as every other human, after all. But they have survived so long without it, found a way of living without math, why start now?

In the book Don’t Sleep There Are Snakes, Daniel Everett tells a story of how the remote Amazonian tribe he is living with, the Pirahã, do not use numbers or math. He tried to teach them simple addition, but they didn’t have any prior experience with the concept of numbers or adding and would not learn. What if for some people, areas of their bodies feel like math did to the Pirahã? They could learn math if they wanted to, they have the same brains as every other human, after all. But they have survived so long without it, found a way of living without math, why start now?